On having a wedding while 34 weeks pregnant, and reconnecting with Native American roots.

Joanna + Geff // Clarksville, Tennessee

“Where’s my baby?”

Joanna looked out the door for her and Geff’s baby son, Lyric, as a few friends arrived at their home for a small wedding after-party. (She and Geff had left the one and a half year old with a trusted friend after the ceremony so they could drive their getaway car ahead of everyone else.) Anthem and Harmony, Joanna’s two daughters, ran around the house playing tag, the sound of their intermittent squeals punctuating an otherwise quiet home.

“Where’s my baby?” Joanna repeated, more distressed this time. “Will someone please tell me where my baby is?” As her friends shook their heads in ignorance, another car pulled up to the driveway. Joanna darted out the open door to see if Lyric was with the new arrivals; she returned a minute later with the drooling, absent-minded baby snuggled between her arm and her belly.

I thought of a similar moment from a few hours before, after Joanna and Geff’s ceremony had ended and as we wrapped up a portrait session. Standing in the center of the open-air pavilion, while talking with some friends, Joanna suddenly spun around a few times, looking for Lyric. When she didn’t seen him, she began frantically calling out, asking if anyone who knew where he was. Darla, Joanna’s mother, called back a few moments later; Lyric rested happily in her arms.

Darla, Joanna’s mother, with Lyric

“I have a tendency to mom everyone,” Joanna wrote to me in one of our first emails, a habit that I learned stems from her deep compassion towards other people. Joanna’s mother, Darla, told me about it one afternoon. “After high school, Joanna got this job doing in-home care for families, and she worked with this family with three women who had Down Syndrome and were of different ability levels. She would go in and help these girls do all sorts of things in their lives.” Darla sniffled, reaching for a tissue. “I didn’t have that kind of compassion,” she said with watery eyes, “but Joanna did, and she loved doing that work. I’ve learned so much from her.”

Darla, Joanna, and Geff after the ceremony

Joanna thinks constantly about the well-being of those around her, often at the expense of her own mental health. “I have significant anxiety,” she told me, “and so I have found that my coping mechanism is panicking.” She laughed, somewhat uncomfortably, and described what it felt like to her. “I know it manifests differently in everyone, but for me, what happens is that my brain goes through every bad situation or scenario, and just plays it on repeat until I have a panic attack.” Joanna began talking faster and faster, hardly taking a breath. “I'm like, well, but this could happen or that could happen or this other thing could happen and then what if this happens to this person and then what if this other thing happens because that happened and…”

She paused, looking for a visual. “It’s like a figure skater,” she described, “spinning faster and faster and getting dizzier and dizzier until she just falls out.”

Joanna grew up in Chico, California, and, as she described it, “came from a really rough background.” Her parents fought a lot; CPS once had to get involved to remove custody of Joanna and her siblings for around a year and a half. She ended up being responsible for much of her own home life.

Joanna, left, pretending to cut her younger brother Brian’s (center) hair along with her sister Odessa (right)

Joanna (right) with her older sister Veronica (center) and younger sister Odessa (left)

When I asked what filled her time as a child, she replied, “I played the saxophone for a little while, but my parents made me stop. I had to take care of my younger siblings.” She sighed. “School never felt like it was long enough, and after it, I pretty much stayed at home and took care of the house and my siblings and everything else.”

When Joanna was 16 years old, she moved with her mother to central California to get away from her father, whom she described to me simply as “creepy and misogynistic.” She dropped out of high school not long after that, and the way Joanna initially recounted the next years was in fragments and quick breaths. “I met this guy. And I got married. And then I had kids. And then we were homeless. And then I moved to Colorado. And then he was not talking to us or helping financially. And I was like, well, I gotta find some way to take care of these kids. So I lost a bunch of weight and joined the Army.”

I began forming a reply before pausing, stumbling over my many follow-up questions. “When I usually talk about it, there’s just so much to unpack that I gloss over everything,” Joanna admitted, perhaps sensing my uncertainty. “I don’t mind talking about it; there’s just so much to say.”

Soon after she left high school, Joanna met her now ex-husband, who was in the Marines. They married very young, right before he was due to deploy to Japan. “It was never a good relationship,” she said. “He cheated on me, and I wanted to leave him before I knew I was pregnant with Anthem”—Joanna’s oldest daughter—“but when I found out I was pregnant, I stayed.”

A year after her first daughter was born, Joanna found out her ex was cheating on her, again. She also found out she was pregnant, again. “I kept staying, because I was financially dependent on this person. I wasn’t allowed to work, and I wasn’t allowed to have friends.” When a service member is stationed a certain distance away from their family, the military provides a bonus called separation pay, which her ex-husband was receiving despite him and Joanna living together. “He was actually so good at hiding me that the military didn’t know,” Joanna said.

The two moved around for a bit, staying first with Joanna’s mom in California and then, when that didn’t work out, moving to Virginia to stay with her ex-husband’s parents. “That was way worse,” Joanna said, leaning her head back to emphasize way, “because both of his parents were alcoholics. At one point, his mom called CPS on me, saying that my daughter was malnourished and living in an unsanitary environment, when we obviously lived with her.”

Joanna, still pregnant with her second daughter, Harmony, began getting visits from others concerned about her situation. “Social services came out to talk, and the woman was so concerned about me going into preterm labor that she gave me the phone number to the safe house for women who are in bad situations and told me I should leave.” Joanna brushed the thought away, wanting to at least stay with her ex-husband despite the worsening situation at home.

“Three weeks after I had Harmony, it got really bad,” Joanna continued. “It was, like, 5 o’clock one day, and his mom was already drunk. I heard a huge commotion downstairs, and then my ex came in with his shirt completely ripped open and his glasses broken.” He’d gotten into a fight with his mom, and told Joanna to take the girls and leave right away to get them out of the dangerous situation.

Anthem holding Harmony during this period of time

"I got the diaper bag, and I left,” she told me. “It was the end of November, early December, and I went to his cousin's house with the girls.” When she got there, the other people looked at Joanna and quickly asked what had happened; in the rush to leave, she hadn’t even put on a coat or shoes.

The months that followed were filled with a maelstrom of unfortunate events. Joanna had an emergency appendectomy; she, her daughters, and her ex stayed in a few hotels paid for by the Salvation Army; and, after calling dozens of shelters to see if any had family vacancies, on New Year’s Day, something clicked in Joanna’s mind. “That’s when I realized: I’m homeless. We’d already been homeless for weeks, but it finally clicked when we got to the shelter.”

Joanna wearing Anthem (left) and Harmony (right) in order to get some chores done at the shelter

Joanna recalled a memory from that time. “When we were leaving the hotel, I remember stealing a blanket from them. I felt bad about that for years, because I'm not that person; I don’t steal things from other people. But I was so scared, and life felt so uncertain, that I stole a blanket just so that I knew that my kids could at least be warm wherever we went.”

The family stayed there for five months before eventually finding an apartment. Joanna’s ex-husband became an over-the-road truck driver and dealt in shady financial practices. “He started using pay advances to pay for things he wanted while he was on the road,” Joanna told me, “and had a credit card I didn’t know about that was maxed out with $8,000 of him paying for strip clubs and hotel rooms.” Joanna worried about how they’d pay the bills for the apartment; her ex-husband suggested she move in with a friend in Colorado so she wouldn’t have to worry about utilities, and said he’d join once the lease to the current apartment ended.

“He never showed up,” Joanna said. “He never talked to us again. He wouldn't answer his phone. I didn't have access to the bank account anymore.” Joanna and her two young daughters were completely on their own, stuck with this “friend” to her ex-husband but a stranger to her. “So I just did the only thing that I could think to do to support my daughters: lose weight, and join the Army.”

Joanna freely admitted that she joined the military for the steady paycheck and the health care; her oldest daughter, Anthem, had kidney issues, and to this day remains very fragile. She also has severe food allergies to gelatin. “Did you know that a two-pack EpiPen for kids costs $630 without insurance?” she asked, registering my shock. “Yeah, so I basically sold my soul to the country so that I could take care of my kids.”

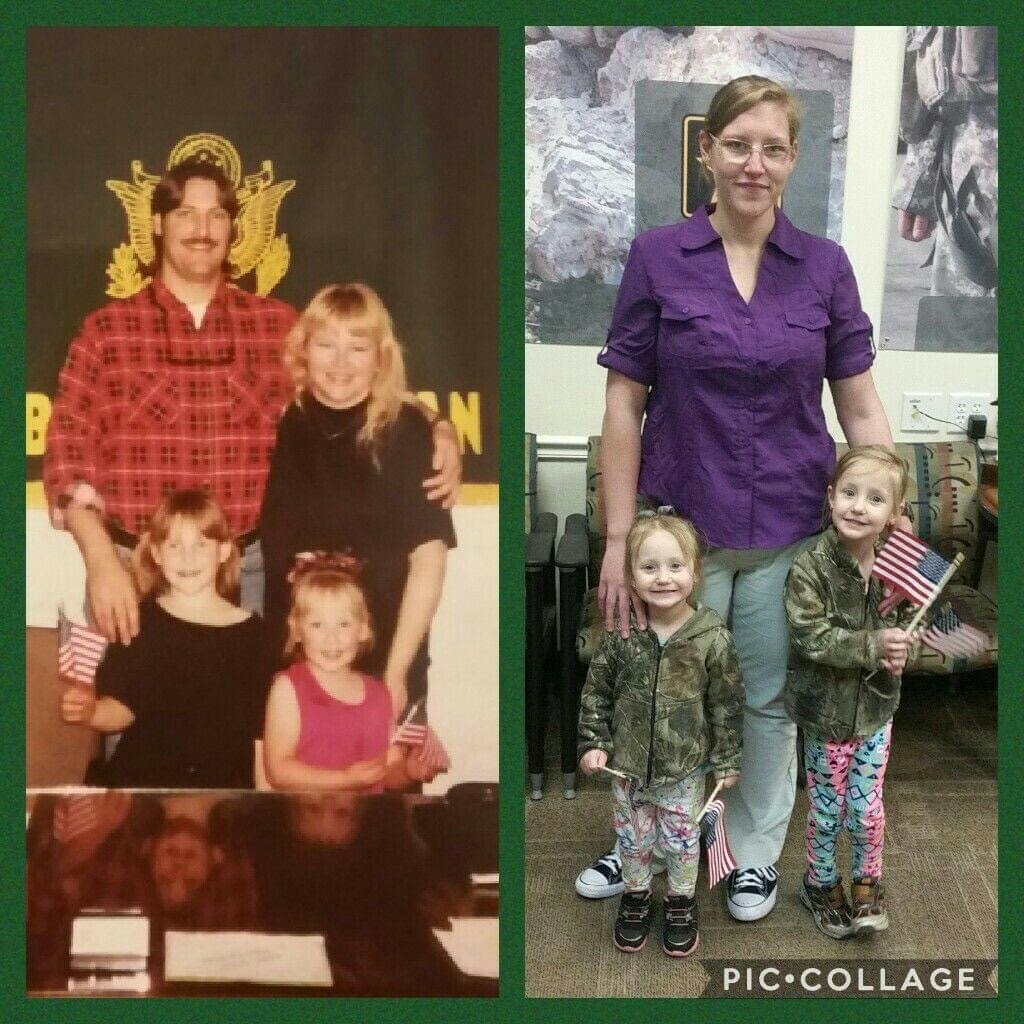

(Left picture) Joanna (lower left) and her sister Odessa (bottom right) with their parents the day their father enlisted in the army. (Right picture) Joanna with Harmony and Anthem the day she enlisted in the army

Joanna was recruited in Colorado, did her basic training in Oklahoma, and went to Advanced Individual Training—the Army’s name for training a recruit does in their specialty after basic training—for Intelligence in Arizona, before being stationed at Fort Campbell in Kentucky. For the eight months she was in training, she had no choice but to leave her kids in the care of this man she’d moved in with in Colorado.

Joanna during Army training

“He tried so hard to be in a relationship with me,” she told me. "I came back to visit once, and Anthem and Harmony were calling him dad. He was using my kids against me, saying I was off ‘living the life of a single woman with no responsibilities while I'm over here with your kids trying to do the best that I can.’” Resentment dripped from Joanna’s voice. “I was sending him $1200 a month, pretty much my whole paycheck, and he also had full access to my accounts. I told him, take anything you need; as long as my girls are being taken care of, I don’t care. Because I was in the barracks; I had food; I was fine. But whatever they needed, I wanted to make sure that they were taken care of.”

Joanna in the Army

In addition to sending money, Joanna also made dozens of meals in advance whenever she got the chance to visit so that he wouldn’t have to spend more time cooking for the girls. “I even bought a new freezer for him to store them in,” she told me. Her plan was always to eventually get her girls so they could permanently reunite, but doubt had leached into her mind. “I was nervous about how I’d afford to pay for their childcare while I was working, and I thought…” Joanna made a rare pause. “Maybe I'm not what's best for my kids, and I need to just let them stay with this guy.” I could hear the pain in Joanna’s voice just imagining having to part with her children.

Anthem and Harmony, Joanna’s daughters

But when Joanna spent a Christmas back in Colorado with her daughters, and “this guy” made particularly unsavory comments about consent and suicide, she decided again that yes, actually, she had to get her kids, and she had get them as soon as possible.

“I came up with this plan,” she said. “I was gonna go out there and get them and come back all in one day, so I wouldn’t have to take formal leave.” She called her original recruiter from Colorado (“I told them the whole situation, and even though this obviously wasn’t in their job description, they helped me,”) to pick her up from the airport and get her kids before driving back to Fort Campbell with them. Joanna’s ex-husband, to whom she was still married at this point, remained absent.

After she managed to get the divorce papers with her ex-husband signed, Joanna never expected to be married again. “I was single for two years, and I just thought, like, I was damaged goods, kind of a thing. Someone once told me that dating a girl with kids is like picking up after someone else’s saved game, and so I wasn't even going to try.”

Luckily, Joanna didn’t have to try. As she described it, “I met Geff, and it was instant.”

Joanna and Geff during a portrait session

The two met on Thanksgiving in 2017. Joanna was recently stationed at Fort Campbell, and didn’t yet have her daughters with her. “I reached out to Facebook asking if I could spend Thanksgiving with someone, because I didn’t want to be alone for the holiday,” she told me. One of her friends with whom she’d gone to basic training invited her over. “My friend and his wife promised to get me super drunk, just for one night, so that I wouldn’t miss my kids so much.” Joanna did her best to hide her emotions during Army training, but she’d broken down on Mother’s Day when she received a card from her two daughters and wasn’t allowed to even call them in response.

She and Geff describe feeling an instant attraction, if not necessarily an instant connection. “I saw her come in,” Geff told me, “and I, you know, straightened myself up, and confidently introduced myself to her.” Joanna, likewise, remembers his smile and his eyes. “We were able to talk about deep stuff really quickly,” she said. “I started talking about my kids, because I don't know how to do anything other than that, and so he talked about the daughter he thought he had,”—Geff was in a fight to determine whether he was the father from a previous relationship, but the child’s mother kept shutting him out—“And it was just normal flirtation. I didn’t know that he liked me back until the end of the night and we were kissing.”

Geff and Joanna ending their first dance. Lyric is flopping around in the background

“There have been a few times in my life,” Geff said, “where I just knew I needed to make something happen, and then I just do it. Seeing Joanna, I knew I needed to make something deeper out of our relationship.” I asked what he meant, knowing that he had to “make something happen,” and how she was different from other people he’d met. “With other relationships, I could always kind of see how it was going to end; the kind of conversation we’d end up having, when we’d have it,” he replied. “I had come to understand that I was usually the in-between for other people, like they were gonna hang around me for a while, get what they needed, and then move on. So I got pretty used to that, and got used to the idea that I was more of a ‘fixer upper’. But that didn’t happen with Joanna; I couldn’t see an ending; it was open.”

Geff and Joanna’s cake cutting

Geff shared a bit more on how he’d see the end of other relationships. “There was a red flag: the other person could only use the terms I and me. I realized that if they can’t think in terms of we and us, then there’s no future. There’s also no communication, because if they don’t think in terms of we and us, then they don’t think they have to share anything about how they feel.”

After meeting that Thanksgiving evening, the two began seeing each other more often. With Geff’s encouragement—he’d pointed out all the problematic things that her kids were being taught—Joanna made the single-day pickup of her kids, and over the next few months Geff began to spend more time with both Joanna and her daughters.

Even before COVID, Joanna and Geff never wanted a large ceremony. “We were looking at a local distillery,” Joanna told me, “and the price was significantly cheaper on a Wednesday than on a Friday or weekend.” She’d told Geff about the price difference, and he responded, “I don’t care what day it is; I just want to marry you.” Joanna booked the venue back in the beginning of 2020. “I got so stressed out within that first week, because we just started inviting people, and it got bigger and bigger, and I couldn’t handle it anymore. So I just canceled the venue, and we luckily got our deposit back.”

The wedding, Joanna and Geff decided, would be more for Anthem and Harmony, Joanna’s two daughters, than for themselves. “They’re getting a dad now,” Joanna said, referring to the custody battle soon coming to an end with Geff legally adopting the two girls. Joanna, only slightly joking, told me earlier in the week, “if you could just get photos of my children and the guests, and not me, then that’d be great.”

Joanna’s daughters, Anthem and Harmony

The two decided to rent an outdoor pavilion at a local park. The open-air layout would be the safest option with COVID-19, and a nearby forested walking path and bridge would make for some nice photos; the playground for the kids was also a convenient touch. There would only be about 20 guests, and their theme would be sunflowers.

Anthem at the playground after Joanna and Geff’s ceremony

I asked if either of them had been nervous having kids before they were married; Lyric, the one and a half year old boy, was theirs, as was Joanna’s current pregnancy. I’ve heard from other couples that getting engaged and married helped them to feel more secure about life and the future. “But why does that make it more secure?” Joanna retorted, unconvinced; “I didn’t feel secure in my last marriage; I felt trapped.”

Around January 2018, Joanna was prepping to deploy to Afghanistan. Geff, having also been in the Army and seen that the distance could break relationships—his prior marriage ended when his ex cheated on him while on deployment—was worried, but the two decided to try and make the relationship work.

“In April, though, I found out I was pregnant,” Joanna told me. “Geff was over the moon, but I had concerns immediately and told him I felt like the baby wouldn’t make it. He kept telling me that he was sure everything would be fine, and that even though we didn’t plan it, that he was excited to start a family with me.” Eight weeks into the pregnancy, Joanna had a miscarriage. “I was heartbroken. He was, too, but he stayed as strong as he could for me. We argued a lot around then because we were both in pain and didn’t know how to handle it. But we both knew we wanted that baby. So, we decided to try to have one, intentionally this time.”

Geff and Joanna during a portrait session

Many couples never fully recover, emotionally or physically, from a miscarriage, so the two were happily shocked when a pregnancy test the very next month came back positive. Their son, Lyric, was born in January 2019, a few months after they’d moved in with one another. As Joanna described it, “After a few months of watching our son grow and learn, getting to watch Geff be a dad, and him getting to watch me be a mother to his son, we decided on a wedding date.”

Before long, in December 2019, Joanna found out she was pregnant again, this time with a girl. The two had just set their wedding date for December 2020, but Joanna expressed how she’d rather be pregnant than have a tiny baby at the wedding. They moved the date up to July 2020, a month before their last child, Rhapsody, would be born; “No more kids,” Joanna told me, particularly fatigued one day at home. Joanna didn’t initially plan for the children’s names to be variations on a theme, but after her first two daughters she and Geff decided to continue: Anthem, Harmony, Lyric, and, finally, Rhapsody.

Geff and Joanna’s whole family

Geff is part Native American, something which has played both a large and a minimal role in his life. He grew up in Virginia, first in Virginia Beach, (“Really diverse, a lot of different cultures and walks of life because it's a military town with Navy, Marines, and Army,”) and then Suffolk (“It was black, white, and very few people, like me, in-between.”) Geff’s parents met in San Diego, where his father, a Navy veteran, was stationed. His mother was part Native American and Mexican, while his father is mostly French. Geff knows relatively little about each of their pasts, especially his mother’s, who he suspects blocked out the memory of her previous life when she moved east. What he does know is that his mother had a difficult childhood.

A memorial for Geff’s mother, Lola

“She quit school in the sixth grade,” Geff told me, "because she knew her problems were not anything school could fix. If she knew the bills weren’t gonna get paid, then she’d go to school, start a fight with a resource officer, and then go to jail so she’d at least have a roof over her head and food.” Her family had been kicked out of their tribe (“I think the Yuki people,” Geff tried recalling) after her mother’s uncle, a Chief, was mysteriously killed by competing members.

Geff has rarely let swipes at his identity bother him. “I came up in a house full of sarcastic assholes, so unless they were being overtly racist to me, I wouldn't catch it.” I asked what other people would call or do to him. “People could kind of assume I was whatever they wanted to see,” he told me. Sometimes, he was Asian, other times Mexican; rarely did people realize he was also Native American. “There aren’t many of us still around, and most, like me, are mixed,” he said.

Baby Geff

Geff in elementary school

He described one incident from when he was a child. “This kid came up to me on the bus, and just said, ‘You need to go back to where you came from, Chink.’ And I was like, hold on. One, you shouldn’t be using that, but Two, I’m not Asian. If you’re gonna use a racial slur, at least be accurate. You could try wetback, border-hopper, spear-chucker; you’ve got a lot to work with, and you’re not even trying.” The other kids on the bus laughed at the offender; Geff hadn’t even been trying to elicit a response. He was just trying to respond logically.

Geff in elementary school

Most of Geff’s nonchalance towards ignorant people seems to come from his own laid-back nature, but part of it also comes from a pride and comfort with his identity. (Humor is also a factor; one day, he wore a shirt that riffed on the Washington football team logo by replacing the prior slur with “Caucasians,” and the image of a Native American with a generic, similarly styled white man.)

At the wedding, in addition to a Celtic hand-fasting ceremony, Geff and Joanna performed a sage smudging ceremony, where Geff’s best-person slowly waved a bundle of the smoldering herb around Joanna and Geff. The ceremony is Indigenous in origin, and is thought to rid negative energy from the space surrounding the couple, allowing a positive beginning to their marriage.

Joanna and Geff at their ceremony

Geff’s brothers are working to regain status within their tribe by testing their DNA and tracking lineages, and the family does what they can to maintain their involvement with the culture. “There was a big powwow we were supposed to go to around the reservation our people are originally from, but it was canceled because of COVID,” he told me with an air of disappointment.

After Geff’s parents divorced early in his childhood, Geff grew up under the same roof with his mom, step-dad, and dad. Seeing my surprise, he tried to explain. “They did it for a lot of logistical reasons, and just thought it was easier for everyone to stay under one roof.” One day, when we were running errands, Joanna joked that most of Geff’s life had been confusing. “His name is Geff, but so was his stepdad’s, and his dad’s name is Glenn, but so is his brother’s.” Geff guessed the arrangement was his dad’s idea. “As flawed of a man as he was, he wanted to be present in our lives,” Geff told me.

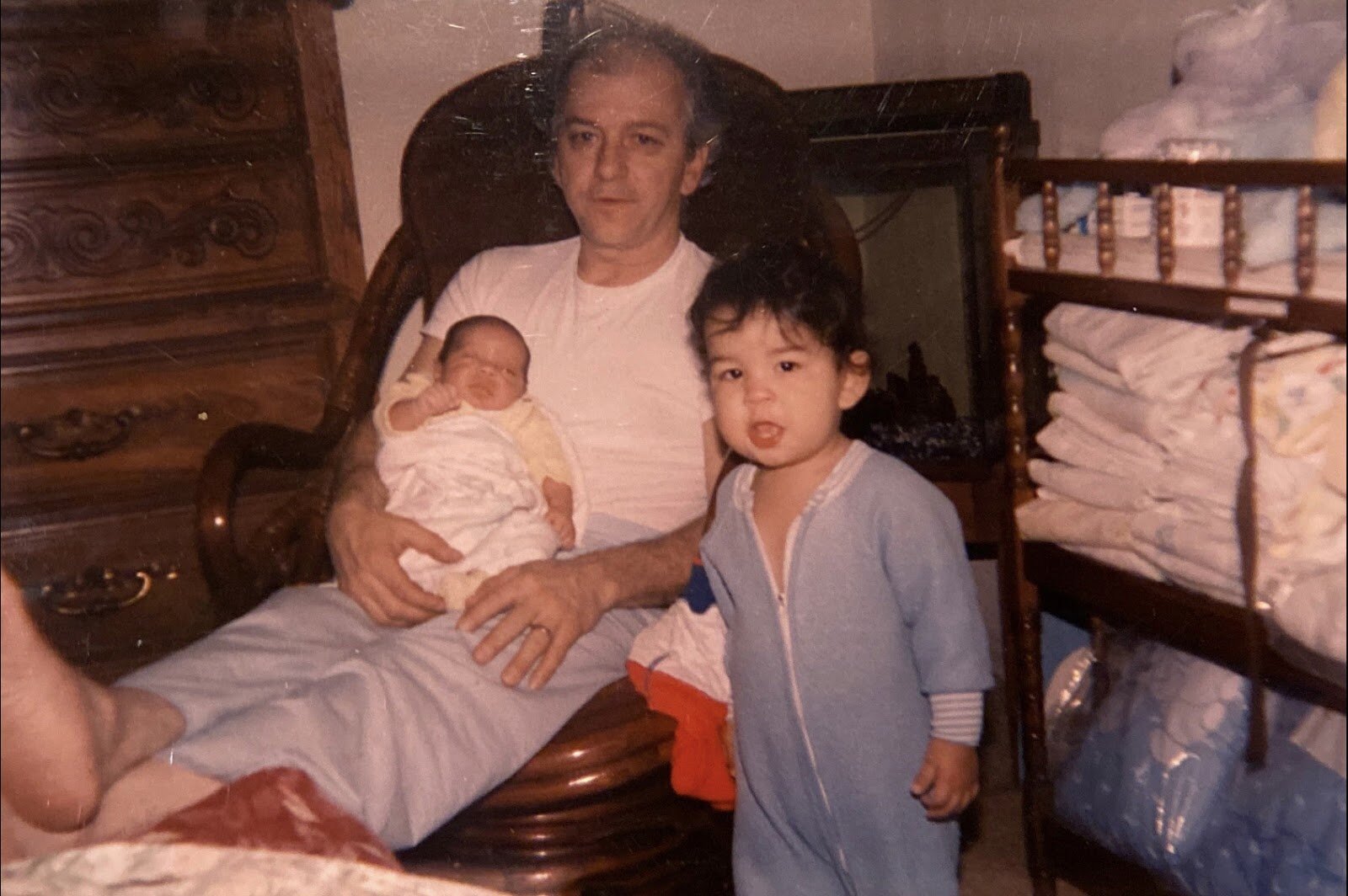

Toddler Geff (blue) with his father

Joanna, Geff, and Geff’s father Glenn

Commotion always filled the home. “We had monkeys growing up,” he said somewhat matter-of-factly. I commented that I didn’t even realize you could have pet monkeys. “It was the worst,” he replied. Geff’s mother had seen someone carrying one out in public; without success, Geff and his siblings tried convincing her that they didn’t need more animals. (They already had ponies, dogs, cats, and a peacock.) “There was a master bathroom, and it was originally set up for a jacuzzi, but they took that out and put in these huge cages. And the monkeys would still get out, and climb all around the house.” He mimed the process of him and his siblings hosing the monkeys down from their high perches, chasing them into a corner, and grabbing them to put back into the cages.

Geff’s mother, Lola, with the family’s monkeys

Lola with one of the family’s monkeys at Christmas in 2007

People filled the home as well. I talked one afternoon with Chison, a close family friend who considers Geff and his brothers to be her own brothers. “I met Lola, Geff’s mom, several years ago and just kind of got integrated,” she told me. “We opened our first restaurant together, and pretty much all the kids were working there at some point, so we just became a pretty tight-knit family. Lola took in every homeless person or animal she found and got them settled, up and going again. I honestly couldn't think of a better person than her, and I really believe that that rubbed off on all her children.”

A memorial seat reserved for Geff’s mother Lola

Her generous spirit did rub off on Geff, as well as a respect for work and money. “I was about 13 when I started working,” he told me. “I wanted this pair of jeans that were $50, and when we were at the mall my mom wouldn’t buy them for me. Instead, that Saturday morning, she woke me up and said, ‘Get dressed, you’re coming to work.’” The family worked in the furniture business, and so Geff’s mother had him assemble various tables, chairs and dressers, an early and much more difficult version of build-it-yourself IKEA furnishings. After two weekends of work, Geff’s mother handed him a $50 bill. “I did get the jeans,” Geff said, “but this time off of the clearance rack so I could save some of the money.”

Geff (right) with his mother and one of his brothers

From then on, he’s always worked for what he’s wanted, and what he’s wanted, he’s always bought. Joanna had recently asked Anthem and Harmony what they wanted to get Geff for Father’s Day, to which they’d replied, “We can't get him anything, because if he wanted it, he would’ve already gone out and got it!” Geff chuckled in agreement recalling the story.

I arrived at Joanna and Geff’s home in Clarksville, Tennessee a few hours before Geff was due to go on one more 24 hour shift as a paramedic before the wedding, after which he’d have a few days off. Over a drink, he told me about how he’d wound up in his job.

High school was rather boring for Geff, and after graduation he joined the Army. “I had all these ideas of going special ops and being, like, badass,” he told me. He paused to think for a moment. “I didn’t really have much ambition after high school, so I guess what I subconsciously wanted out of the military was direction and drive.” He told me a story from his time in basic training. “When you first show up, they do what's called a Shark Attack. Basically, drill sergeants will just descend upon your group, berate you, confuse you, yell in your face to hurry up.” Geff’s face lit up as he told the story. “It was everything that I expected, and I thought it was great. Like, I was trying to hold back my laughter, while other people were crying their eyes out.”

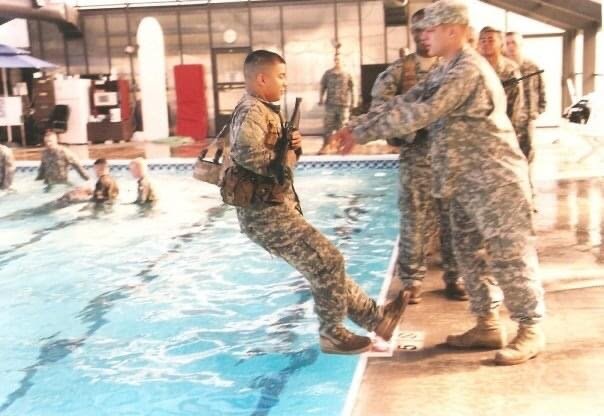

Geff in training

He joined the Army Reserves when he was 17 (his mother wouldn’t give him permission to enlist under active duty at that age) and was offered two paths: “computers, or medicine.” He knew nothing about computers, so he chose to be a medic, starting on a 16 week training course. His first six weeks were standard EMT training. “One of the things the Army pushed was marketability, so they’d try and get people certifications and everything,” he told me. “After we went through that course though, they said to forget everything we just learned, because on a battlefield, we’d get people killed.”

He described the differences being mainly detail and speed. “On the civilian side, things are a lot more methodical. In the Army, you have what’s called TC3, or Tactical Combat Casualty Care.” The process sounded much like a flow chart. Are you under fire? If yes, fire back. Is the soldier able to respond and care for themself? If yes, have them do that. Does the soldier have a more major wound? If yes, throw a tourniquet on it, and drag them out of combat.

Geff during training

Over his 12 years in the Army, Geff deployed to Korea, Iraq, and Afghanistan. He once flew in helicopters with a medical evacuation unit, but more often stayed close to the ground and out of any direct combat. “We maintained small clinics to conduct pre- and post-deployment health assessments,” he told me, “and gave out lots of immunizations.” He blanched while sharing a story about an old unit, the 86th Combat Support Hospital (CSH), known as the 86 Cash. “I joined when the unit just came back from deployment in Iraq, which was the deployment in the documentary Baghdad ER.” Many of the people, he felt, were arrogant from being in the movie.

Geff during this period of time (you can see the unit crests on his sleeves) with his maternal grandmother, Frances

Geff (right) with a fellow soldier on deployment

As someone who grew up with virtually no friends or family serving in the military, I had long assumed that working there must be entirely different from working in the civilian world, an assumption that likely came from movies and TV shows that heightened the action and downplayed the boredom.

In some ways, those assumptions were true; service members and their families certainly make sacrifices few civilian jobs require through deployments and strict codes of conduct. But work is work, and a job is still a job, complete with internal politics and the constant balancing act of trying to find fulfillment in one’s work and in one’s personal life at the same time.

Geff on deployment

And so, of course, Geff’s decade-plus in the Army had periods when he did poorly (“I don’t really know what happened, but I turned into a piece of shit for a while, always being late and having to clean up my act,”) and periods when he did well (for which he received promotions.) He ultimately decided to leave after a negative experience working with his final unit. “I was up for reenlistment in 2013,” Geff told me, “and I said that I’d reenlist today, but not with that unit.”

When the Army couldn’t guarantee that, he decided it made sense to join the Kentucky National Guard and return to a mostly civilian lifestyle. At 27, he enrolled in college for a double major in Biology and Sociology (“I tell people all the time, school was so much harder than it would’ve been if I were 18,” he said) and after a few turns through starting his own massage therapy business and other jobs, he went to paramedic school and began working on ambulances, with many of the lessons he learned treating trauma cases in the Army carrying over to the civilian job.

“Back in the early 2000’s,” Geff told me, “civilian EMS didn’t have aggressive teachings for major hemorrhaging. But ‘lessons learned’ about trauma over the years of combat in Iraq and Afghanistan worked their way into civilian EMS patient care.” The military, he said, took their cues from the civilian side for treating more standard medical issues, while the civilian side took cues from the military for trauma.

Geff with Anthem and Harmony after graduating from paramedic school

Geff with fellow massage therapist students during a group outing

Geff enjoys his work; we spoke at length about memorable times when patients have overreacted (as with a lady who had a broken ankle repeating “I don’t want to die,”) or under reacted (as with a soldier refusing morphine after his foot had been blown off from a mine, more worried about feeling sleepy than quelling his pain).

When I asked about his own headspace on the job, fear was not in his catalog of emotions, but nerves certainly were. “It’s more logistics,” he said, “like if I were about to go on stage to do a performance, and would worry about doing something wrong.” He admitted to a handful of situations in his medic career where he reeled with emotion, but he doesn’t dwell on them. “They sometimes come around,” he said of those memories, “but in the same way some random memory from my childhood might come back around.” Mostly, Geff was the type to crack jokes or make puns, even in serious situations.

Geff with some of his coworkers

“There was once someone who had an asthma attack while she was at kickboxing.” Geff began. “By the time we got there, she’d taken out her inhaler and was doing fine, but was still in a bit of a panic because of her anxiety. So I ended up not doing anything for her, but just sat there and listened to her.” When he returned to his truck, he shared the story with his coworker. “I told him it was from kickboxing and said, ‘I guess she got the wind knocked out of her.’” “So she got slammed down?” his coworker asked, not understanding Geff. Geff tried one more time, waving his hands for dramatic effect. “Let me rephrase. It took her breath away.” His coworker was less than amused.

“It’s chaos at our house all the time,” Joanna told me during a rare second of rest one evening, shortly after she and Geff had put the kids to bed. “Yesterday, Lyric came in here, dumped all of the balls out, took that cushion off of the couch, and then flipped the other table over.” She pointed to each, one by one, as if giving cues to an orchestra. “And I was like… Okay? And now just imagine you are alone with three kids, and you go to the bathroom and come back out and see all that. And that’s every day.” Joanna shrugged at me, offering some advice. “So, if you're ever thinking about having kids, just remember that's how fast it happens.” I made a mental note.

Harmony, Lyric, and Anthem at home one day

Anthem and Harmony, the two oldest of Joanna and Geff’s kids, have ADD and ADHD, respectively. I asked before we met in-person what their personalities would be like. “Medicated, or unmedicated?” Geff asked me. “Because when they're medicated, they’re totally different, which I think are their true personalities.” I saw the daily ritual; the kids would wake up at around 7am each morning and embark on a general mission of demolishing the home and silence around them. At breakfast, they’d take a few bites of their food, become distracted, and only after Joanna raised her voice take a few more bites of food. After that, they’d take their medication.

Anthem and Harmony playing around with my camera

The girls would then calm down significantly and spend the rest of the day doing activities. I was raised an only child and never had many other extended family members around me, so in many ways the environment of a chaotic household was foreign to me. I asked Joanna what the most noticeable change in their behavior was after they took their medications each morning. “What they were doing just now? Staying in one place, having a conversation, coloring for a while; that’d be impossible if they weren’t on their meds.”

Harmony and Anthem finishing up a coloring session at home

Where Anthem and Harmony, seven and five respectively, could be somewhat contained through medicine, Lyric, one and a half, could not. He would often flounder about until someone put on a favorite show, Cocomelon, a multi-hour series of songs that teach basic words and concepts—numbers, ABC’s, potty training—set to a cast of dancing, smooth-skinned, plainly animated characters. The program repeated so often at home that I wondered if Joanna and Geff ever thought they were descending into some baby-inspired fever-dream.

Lyric and other family at home the morning of the wedding

As the three kids played with one another, Joanna took note of every out-of-place yip, squeal, or chance of harm. “Anthem once punched Harmony in the face during one of her outbursts,” she shared with me, “Harmony got a bloody nose after that, and in the weirdest moment of clarity, took off her shirt so the blood wouldn’t drip on it.” When Geff saw her, he first asked, “Why aren’t you wearing a shirt?” “When I saw her,” Joanna followed, “I was like, but why are you bleeding?”

Joanna and Geff’s current home is clearly a bit small for everyone there: Joanna, Geff, Anthem, Harmony, Lyric, Rhapsody on the way, and Joanna’s mother, Darla. After Joanna gets out of the Army, they hope to buy some land in Virginia where they can build their own home. “We’re looking at properties to move to that are at least 20 acres,” Geff told me. “The plan is to beat down some trails and plant along them; different fruit trees, berries, nuts. Maybe set up a shooting range somewhere, or four-wheeler trails.” The home would be closer to many of Geff’s family, while the land would provide much-needed space for their children to play.

Joanna and Geff playing with Lyric one afternoon at home

Joanna had been working from home during the pandemic for her Army job in Intelligence—she’s diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis, a rare form of arthritis in the spine, the medication for which causes her to be immunosuppressed—but she’s trying to leave the military as soon as possible. Speaking about her career plans after getting out of the Army, Joanna told me that she hopes to be involved in pediatrics in some way; children hold a special place in her heart.

“I want to be in the Special Victims Unit, or specifically dealing with trauma,” she told me. “Not a lot of people want to think about pediatrics or deal with pediatric special victims, and I know it’s hard, but they need attention, too.” Joanna thought back on her own upbringing. “I always wanted to work with kids. I went through a lot of stuff, but I always know it could’ve been worse, and I always wanted to be there for those that had it worse than I did.”

She’s currently working towards a forensic psychology degree, and before then also plans to get certified as a Registered Nurse. “For now, though, I just really want to be at home, with the kids, and get out of the Army.”

Joanna doing Harmony’s hair for the wedding while everyone watched TV

Joanna and Geff’s after-party following the wedding had been a short and unpretentious affair. Most people grabbed a drink or two, made quiet small talk, and wished Joanna and Geff well before heading home. Anthem and Harmony spent most of the night running around or playing on a recently installed swing on the back porch; by the end of the night, they’d figured out the best way to twist the supports so that they’d spin as quickly as possible.

Anthem and Harmony playing with a swing on the back porch

As most of their guests filed out, Joanna, Geff, and I sat on the back porch and talked for a while longer. Geff was visibly drunk, his words a bit lagging and slurry. He spoke to no one in particular. “My mom would’ve loved you like she birthed you herself,” he said. “She was the best. I watched this special with Oprah… who did this whole thing with a pastor, and said: 10 gallon people… can’t love 100 gallon people. So me… you… we love like there’s no tomorrow… because we have so much love to give.”

“That’s not really how it goes,” Joanna said softly, rolling her eyes and smiling. “Super close though.” “He’s trying,” I shrugged and grinned back. Geff paid us no mind. “But the people around us… are often two, three gallon people… and they love us to the capacity that they’re capable… but we want and need so much more… because our ability to love is so much greater.”

“Drink water,” Joanna interjected, taking Geff talking about gallons as an opportunity to help him sober up. Geff took a long gulp from the water bottle Joanna brought him. “I love you, like you were breathing my lungs. All day long. 100%.” He kept this last part up for a few more sentences, tacking on “all day long” or “100%” where a sentence might need embellishment.

He looked at Joanna, and stared for a few seconds. “You’re so beautiful,” he said, sighing. It was too dark to see Joanna’s reaction.

“I’m so buzzed, someone’s gotta finish this for me,” he said, swirling his drink around. “We love… all day…” Joanna’s brother-in-law stepped in. “Yeah, it can be too much sometimes,” taking his drink from him. “Oh my gosh… so much,” Geff replied. I wasn’t sure if he was talking about the drink, or talking about love.

Geff and Joanna’s brother-in-law, Adam

Geff stood up, suddenly aware he needed to sleep. He looked at me. “Vincent… love you,” he slurred.

“All day long, 100%,” I replied.

The sound of Joanna’s laughter hung in the air as she guided him back inside the house to bed.