Davar and Dacia identify as Black, Mexican, and Christian. They also refuse to be defined solely by those labels.

Davar + Dacia // Pasco, Washington

Each Christmas, around her birthday, Dacia reflects upon the past year of her life; what’s changed about her personal relationships, what she’s accomplished professionally, what went well or what went poorly. Then, she looks forward, setting new goals and imagining what life might look like in another year’s time.

In December 2018, her annual habit brought about a very particular vision: a life partner. “I had the overwhelming sense and feeling that by this time next year, I was going to have already met and be with my future husband, if not already married,” Dacia asserted. “And I was totally single.”

Dacia calling Davar to pray before their ceremony

Her guiding question was simple: how long does it take, really, to get to know someone, and to fall in love? “I guessed that it doesn't take that long,” Dacia said, “especially if you're both willing to be open and you both have the same core values.”

With strong intention and an equally strong filter, she thrust herself into the dating world, joining a few matchmaking groups for Christian singles on Facebook. When someone, trying to liven the community by actively pairing people together, tagged her with Davar, both remembered that they’d actually been tagged together once in 2017. The conversation then had fizzled out, but this time was different.

Davar and Dacia after their ceremony

“Dacia commented saying that I was definitely not interested in her,” Davar said, referencing the previous fizzling out. “I asked what gave her that impression, and she mentioned I had left her on ‘read’. I replied that it'd be better not to receive a message at 2am when I was already about to go to sleep.” The two apologized to one another, and began some flirty banter.

A few days later, they exchanged phone numbers, and their first conversation lasted for seven hours. “SEVEN HOURS!!” Davar said. “I had never spoken to a woman that long on the phone before in my life.” Neither knew at the time that they were both taking time off from work to stay on the phone.

Dacia picking up Davar from the airport in Pasco, Washington

When I recounted this story to Dacia’s younger brother, Matthias, he added, “They brag about that seven hour long call, but that wasn't the only one they had. Me and Dacia’s rooms are right next to each other, and the walls are very thin. So yeah, I heard, Every. Single. Call.”

Dacia and Davar after the pronouncement of marriage

Dacia grew up in Pasco, Washington, which together with the communities of Kennewick and Richland form the Tri-Cities region in the southeastern corner of the state. The area’s fast-growing economy relies heavily on agriculture—wheat and grapes for wine are especially common—and a long-standing government cleanup effort from a Cold War era project to produce material for nuclear weapons. The average citizen’s political views lean conservative compared to someone in bluer parts of the state. (The county this year considered an initiative to secede from Washington and establish a 51st state.)

Dacia moved there when she was eight years old after her father followed a calling to minister Christianity to the area’s underserved Hispanic population. Her mother worked at the local health department while her father built the church’s congregation; his efforts paid a grand sum of $3,500 the first year. “We lived in a warehouse for two years,” Dacia told me, “with no A/C and no heating, in a place that goes above 100 in the summers and below 0 in the winters.”

Being poor in means did not, however, mean the family was poor in generosity or hospitality; I soon found that they were well-practiced in welcoming strangers to their home. On the night of my arrival, Dacia’s father, Andrew, picked me up from the airport. After a short drive—"Everything’s basically max 20 minutes away here,” he commented to me—Dacia and her mother, in the middle of experimenting with how to put up Dacia’s waist-length hair for the wedding, welcomed me to their home with big hugs, and showed me to the room they’d prepared for me. It was down half-a-dozen stairs from the first floor, and came complete with an air mattress, a towel, snacks, and a curtain in front of the stairs to offer some privacy. It wasn’t a necessary gesture—floor or couch space is all I ever ask for—but I certainly appreciated their efforts to make me feel comfortable.

Dacia with her mother and dog while they experimented with Dacia’s hair

As I unpacked, Andrew told me about how he’d often travel around the world to preach, preferring to take his family with him and financially breakeven than to go alone and make a profit so that everyone could experience travel. The family often stayed in strangers’ homes, and in turn hosted strangers, usually other evangelists and their families, when they passed through Pasco.

“We could be on the worst side of town, and a lot of my friends would still come over because they said they always felt comfortable there,” Dacia said, adding with a small laugh, “though, they might not feel comfortable getting there.”

“My family knows what it means when somebody walks into the house,” Dacia continued. “There’s a protocol. We make sure they’re comfortable, that they have something to eat or drink, that we ask about the temperature and if it’s too cold or hot.” They were simple things, but they worked, and I was grateful for the family’s decades-long experience with hosting strangers, soon-to-be friends, like me.

Dacia with her brother, mother, and father

Despite growing up in totally different parts of the country, Dacia and Davar’s upbringings were quite similar. “The midwest was pretty similar to Pasco,” Davar told me, referencing his own upbringing in Ohio, “in that you go to school, get a degree, get a job, build a family, all that stuff.”

Both were surrounded by large families—Davar’s father is one of five siblings, while Dacia’s father is one of seven and her mother one of eleven—and grew up with a strong foundation in Christianity and a stronger sense of love from their parents. “Before I was 16,” Davar told me, “I honestly thought my life was like a fairy tale. My father was a very, very loving father, and my mother is still my biggest cheerleader today. I lived in a two-parent home filled with love, had friends, was smart, played sports.” He offered a comparison. “Maybe like The Cosbys, only not quite as light-hearted.”

Davar with his siblings and parents

Davar’s father worked at Jeep while his mother worked as a social worker, and together they made enough money to send Davar to a Christian private school. They did so to surround Davar with people of similar beliefs, and to give him a better education. “I was the geek in my family,” Davar told me, “the dork, and first generation to go to college. I was very astute, and spoke what other people around me said was ‘talking white’ kind of a thing, just because my teachers would correct my grammar in school.”

Davar credited his early educational success to pride. “The fact that my mom was my biggest cheerleader,” he said, “and that if you give a kid praise for doing something good, they're gonna continue to do it. I think that's what stuck with me as a kid. Not the fear of failing, but the accolades for doing well.”

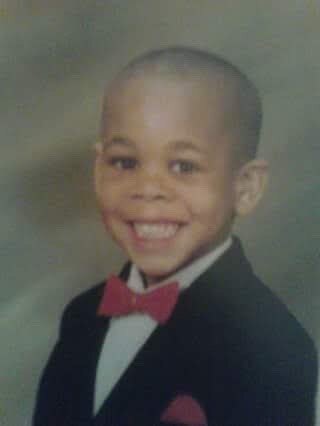

A young Davar

He also suspected another element in his parents’ choice to send him to private school. “I don’t want to have to tie race into this,” he qualified, “but as a Black person in this country, you kind of think whites have it just a little bit better. So, if you send your kid to school among the whites, maybe they can have life a little bit better as well.” He tiptoed around speaking about the inner-city public schools in his area, and how rough many of the neighborhoods were around them. He also qualified that he wasn’t certain whether race really was a factor for his parents.

Dacia’s parents made a similar choice for her education, sending her to a private elementary school, and hoping to give her the space to be a child for as long as possible. She transferred to public school a few years later when the family couldn’t afford the tuition anymore.

“It was like night and day,” Dacia told me. “One day, I was the minority as a Hispanic kid and the poorest kid in school, and the next day I was in the majority. All of a sudden, I was in the same economic group as everyone else’s family. We all knew the same struggles, and we all lived the same way.”

Davar and Dacia both did well in school, and the choice to go to college was clear. Davar first entered school to become an obstetrician (“I’ve always had a fascination with pregnancy and human life,” he told me) but soon switched to photography when he found far more meaning in photographing and working with people.

“College was where I lived in a multi-world identity,” Davar told me. He compared the experience to the superhero Wolverine, who lived through multiple generations, wars, technologies, and lifestyles. Davar’s parents had divorced a few years earlier when he was 16, and the split marked the first time he had to question what had been an idyllic life. That questioning continued in college, when he changed from majors, and after, when he moved out to California to build a career in L.A..

Davar waiting for the ceremony to begin

Dacia, meanwhile, went to school for Business Administration. Her motivations, which she drew from her parents, were clear: though her religion touted that her future husband would provide for her, she and her parents believed that she should still educate herself and learn to be independent, if only as a backup plan should something happen to her future partner. “Since she was little,” Rachel, Dacia’s mother, told me, “we always told her, if you have your Bachelor’s degree, and you go into a successful marriage and don’t need it, that’s perfect. But if he gets hurt, or leaves, you need to be able to take care of yourself and your children.”

Dacia chose a school close to home that she could afford without having to ask her parents for help, and after college searched for a way to engage her more creative and entrepreneurial minds. “At first, I tried to find the ‘career’ job,” she described to me, “and it took me a long time to get away from that. I’m very entrepreneurial, creative and goal driven; I love rising to a challenge. But here,” she gestured around her, referencing Pasco, “that's not what women do. The goal for women is to get married and have a house and have babies and be a stay at home mom. But my dad raised me like I was his oldest son, even though that was not typical for Hispanic families, and because of that, I became really independent and driven, career-wise.”

Dacia and her father beginning the walk down the aisle

Dacia worked all throughout college to cover what her financial aid didn’t, and found the years working in education to be especially fulfilling. “I went back to my old middle school for a program that educated the kids about college,” she told me, “and I remember talking with the kids and being like, I went to this school.” Dacia became more animated as she recalled the memory. "And every now and then, some of the kids would look at me, and you would just see it in their eyes thinking ‘Wait, you were actually here? You went to college?’ It was always really, really rewarding.”

Dacia spent most of her 20’s working different jobs in youth work, refugee resettlement, and education, traveling around the world for work, and for her own fun. (She’s savvy with a budget and with credit card points.) She told me that money, and the stability that came with it, was often the goal. “I always thought that if, God forbid, I got pregnant as a teenager, I needed to make sure my child did not end up in poverty. Or if I ever got pregnant as an adult, and for whatever reason the guy didn’t stay, I needed to make sure I could at least provide a middle-class life for us, because I did not want my kids to grow up in poverty.”

Dacia started a freelance marketing business a few years before she met Davar, but always kept her day job. She moved to LA near the start of the COVID-19 pandemic—Davar, better career opportunities, and a love for surfing were all big factors—but when she was furloughed realized, with Davar’s encouragement, that she could do a ton more with the business than she’d previously thought.

“There's a quote that I love,” Dacia said. “If you want to go fast, go alone. But if you want to go far, go together.” She looked towards Davar. “I feel like we're each other's biggest cheerleaders now.”

Davar and Dacia after their ceremony

Davar and Dacia’s wedding was among the only that I photographed at a formal venue throughout the entire pandemic; most couples planning weddings in 2020 had opted instead for backyards or local parks. The two decided that it’d be held in Pasco, where much of Dacia’s family lived, and where most costs—venue, food, decorations—would fit within their $5,000 budget.

On Thursday evening, two nights before the wedding, after Davar’s family had flown in, Dacia’s mother and father hosted a small get-together in their backyard to welcome Davar’s family to the area. The two families had talked before over FaceTime, but never met in-person, and so the event was designed to let everyone get to know each other before the wedding.

Dacia and Davar’s families gathered in the former’s backyard for a welcome dinner

Dacia’s mom spent most of the day making dinner: rice, salad, and chicken, topped with homemade mole (pronounced moh-lay), a dark, fragrant sauce made from Mexican chilis, whole spices, and unsweetened chocolate. Her dad brought out a set of tables, chairs, and a small tent from their backyard shed, strumming his guitar during an occasional break.

Dacia’s mother cooking while her father took a break by playing on his guitar

Dacia’s brother, Matthias, MC’d the evening, calling out questions about Dacia and Davar, followed by four numbered answers to choose from. Among the questions: ‘If Dacia and Davar could live anywhere in the world, where would they live?’ (France), and ‘How many children do they want?’ (Five, to which someone replied, with laughter, “That’s exactly what someone with no kids would say!”)

Dacia and Davar revealing one of their answers to Matthias’ questions

Dacia’s mother, Rachel, made a short speech and shared a story. “I found this the other day at the store,” she began, looking at the object she held in her hand, “And I thought about my Dacia.” She turned to her daughter. “We used to just call you ‘Day’ at home, and I saw this little plaque, Davar, and I thought of you right away.” She read the engraving while facing Davar. “It says, ‘You Are The Dream to My Day.’ And that’s what you are, Davar; the dream to my Dacia’s heart.”

Dacia’s mother showing Davar the small plaque she got for him

Dacia and Davar noted early, and often, about how faith formed the foundation for their relationship. “I grew up hearing my parents’ love story, and I idolized their marriage and the faith they had,” Dacia told me. “They met in-person, but were then long-distance for two years, married right after that, and are still married today.” Dacia’s mother, Rachel, told me about her thoughts on marriage one day in her car while we ran wedding errands. “I strongly believe that God is the glue to a marriage,” she began. “You have to remember that every marriage is going to have its ups and downs, thick and thins, and those thick and thins don’t just last for a few weeks. They can last for years. And so you need to find somebody who seeks out God, and will pray when you can’t understand each other and just want to hang the other person.”

She and Dacia’s father, Andrew, met in their early 20’s at Dacia’s father’s church. Andrew was at that point a hardcore rock-and-roll band member, and attended service one week to make his friend shut up about inviting him every week. The sermon ended up changing his life, and he never looked back to his old life. When I asked whether Rachel had ever been nervous about Andrew dropping his faith as quickly as he’d picked it up, she answered, “He said to me, ‘Would a person who has thrown up and cleaned it up ever want to go back to that throw up? Because that’s the best way I can describe the life I had before. It was like a bunch of throw up.’ ”

Dacia with her mother, Rachel

At home, Andrew told me stories about his faith and the miracles his family had seen while following it. “The church in Pasco started in a warehouse,” he told me one evening, “and I grew it by speaking to people on the streets, people who were literally drugged out and under bridges, risking my stupid life to bring them to church.” He said this with self-deprecating pride and humor, and no small amount of heartache; he’d shared earlier that he was soon retiring from pastoring, and that the church’s membership had plummeted to near zero since the onset of the pandemic.

Dacia with her mother and father

He also told me a story from when the family lived in the warehouse, and had a big cockroach problem. “My wife told me, ‘I will follow you anywhere and everywhere, but I absolutely can’t live where there are cockroaches.’ We couldn’t afford an exterminator, so I just said, ‘We’re going to pray.’ And we prayed, and prayed, and the next morning, I got up, and turned on the light, and I was shocked, because there were thousands of dead roaches, all over the place.”

“I don't even believe that story,” Andrew sighed to me in mutual disbelief, “but I have so many stories like that.” (Dacia had told me the same story during an earlier conversation. The event was as poignant in her mind as it was in her father’s.)

The seed of Davar’s faith also germinated in his childhood, and, like Dacia, was planted by his parents. “We have this scripture that says that you’re called by God to follow Him,” Davar said, “that you receive the Holy Ghost, and then Jesus lives inside you directs you to truth and better understanding. My faith was kinda chosen for me, because both of my parents had received that.” Davar’s mother became a Christian soon after Davar was born, and for as long as he can remember, his life has been shaped by faith. He attended church regularly, went to faith-based camps in the summer, and even formed a Christian rap group with his brother and cousin.

His faith waned towards the end of high school, when his parents divorced and he no longer regularly attended church, but in college, when he found one or two spiritual mentors, “all the words were already in me, and now it was just bringing it all to life, and gaining more of understanding right now.”

As Davar continued to grow his faith in L.A., building a career in fashion photography and taking background acting gigs in shows like Grey’s Anatomy and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, some questioned his commitment to faith. “I remember posting an image on Instagram, where I’m also professing Jesus as my Savior, and I put a black bar over this woman’s nipples for a photoshoot I did. And someone asked, ‘How can you post something like this, and call yourself a Christian?’ ”

Davar has wrestled with whether there is, in fact, a contradiction. “Every man's struggle is different,” he began, “and I want to protect other people’s salvation. I want to be an artist, to have my work be shown, but sometimes I wouldn't post because I wasn’t sure how it’d be received in the Christian community.” He recalled a moment of clarity at a Christian conference he once attended. “I told someone what I did, and kind of held my breath, when he replied enthusiastically, ‘Wow, so you’re a spy for the gospel, huh! ’”

Today, neither Davar nor Dacia believe their faith and their work are somehow in conflict. Davar put it as, “The way we Christians sometimes feel is that things are completely off limits; being rich is off limits; being an actor is off limits; being in the fashion world is off limits. But I think that just because I’m a fashion photographer, doesn't mean it's a sinful thing.”

Dacia jumped in. “I think that's one of the reasons why we're drawn to each other, because the way we look at Scripture, it says to live in the world, but not of the world. The majority of the church that we've grown up with interprets that as ‘live in a bubble.’ But we look at it as ‘Christ is in me,’ and I can be everywhere and be a believer. And just because a certain place is someone else’s struggle doesn’t mean it’s everyone’s struggle.”

“We just feel called to love people,” Dacia concluded. “And that means we can't pick and choose because of who they are, or what they do. Love people. That's it.”

A few months after Davar and Dacia began talking, in May 2019, the two decided to meet in-person for the first time at Portland, Oregon, Dacia driving down from Pasco, Davar flying up from L.A.. “We spent two days there, and it was as if we’d been in a relationship for longer than the two months we’d been talking,” Davar said. The two shared their first kiss at the airport on Friday, and drove up to Pasco on Sunday to go to church with Dacia’s family.

“I’d never really been in a long relationship until Dacia,” Davar told me, describing his mid to late 20’s personality. “I liked being alone. My favorite local scenic location as a photographer was a desert because it was so barren. Even with Dacia, I still like doing things on my own.”

Davar trying on his suit a few days before the wedding

“I think that's the beautiful part of the way we met,” Davar continued. “Our dialogue started with Dacia being very intentional that she was dating with the intention of marriage.” “I told people,” Dacia said, “I’m not the girl you date to just date, I’m the girl you date to marry.” “Dacia was really getting into telling people about who she was,” Davar followed. “And when you finally find somebody who’s willing to be real with you, it's an interesting thing.”

Their next in-person meeting was in L.A. for 4th of July weekend. The two shared their first “I love you’s” with one another, and spent the weekend surfing and attending Dacia’s cousin’s wedding. “She had a Polaroid camera, and we took a picture that came to be, and still is, our favorite picture together.”

The polaroid picture from Davar and Dacia’s first weekend in L.A.

Dacia met Davar’s family soon after—“My family really liked her and my mom LOVES her,” Davar said—and Dacia moved to L.A. in September 2019 to be closer to Davar. Davar proposed in January 2020 while the two were ice-skating.

“I've been taking little videos on my phone of us since the beginning of us meeting in person and our relationship together, so it wasn't out of the ordinary when I asked someone to record for me,” Davar said. He’d added a diamond to Dacia’s grandmother’s wedding band to use as the engagement ring, a fact Dacia noticed through tears when Davar proposed in the middle of the rink. “We received lots of claps and congratulations, and I told her about her cousins hiding in the crowd,” Davar told me. “We took more pictures and they bought her an ‘I said yes’ T-shirt. It was a joyous night indeed.”

Davar and Dacia after the proposal

When I write a couple’s story, my goal is to always write as if my audience is of only two people: the couple. Doing so is a safeguard against selfish motivations, which, however much I try to keep out of a story, invariably nudge their way into my mind over the course of writing. “What topics in the couple’s life are the most outwardly unique?” “What details about their relationship would draw the most attention on social media?” “What drama, or trauma, from someone else’s life can I use to most benefit my own goals?”

Even thinking about these questions makes me emotionally gag. But, writing for an audience of two means the question I ask myself is no longer “how do I want to portray a couple’s story,” but “how does the couple want to portray their story?” Sometimes, the answer to these two questions lines up; other times, though, it doesn’t.

For Davar and Dacia, the topic of race and ethnicity seems to lie somewhere in the middle of this balance, tipping between any number of thoughts and emotions depending on the context. “Race is important to us as individuals,” Davar told me, “but not to us as a couple.” He confidently emphasized his next sentence. “You could write about our love story, and people could assume whatever color they want us to be. Together, it’s not a Black and Mexican thing; it’s a Davar and Dacia thing.”

Davar and Dacia together after their ceremony

“But individually, I’m Black. I go back to my family, and we’re Black. We do Black things. And the same is true for Dacia. She’s Mexican, and when she goes to her family they’re also Mexican and do Mexican things.”

On our first call together, Dacia shared with me the stories of her grandparents before she shared anything about herself. Both sets of her grandparents immigrated from Mexico, and from poverty. “My grandmother on my dad’s side actually used to be rich,” Dacia said. “They had property, servants, everything. But then her dad died when she was young, and they lost everything.”

A photo hanging in Dacia’s family home of her paternal grandparents

Her grandmother was full of life. “Jolly, beautiful, like you see her younger pictures, and every age, every decade, whatever era she’s in, she’s just grace and beauty.” Dacia remembers seeing pictures of her grandmother as a kid and thinking, ‘My grandmother's beautiful, so since I come from this family, maybe I’ll look good, too!’

Her grandmother was half Indigenous, and was once scouted to be in a John Wayne film. "She was gonna be one of the actresses,” Dacia told me, “but she would have to leave her husband and kids for three months to go on set, so she just refused. She was like, ‘No, I have children. I can't leave them.'” When the movie came out, her family would ask, “Which person were you going to be?” “Oh, it doesn’t matter,” she’d joke back, “they were just gonna put me as the dog.”

“My grandfather was dirt poor, but pursued my grandma like no other. Eventually she fell for him. He wasn't a perfect man by any means. But he truly loved his wife.” Dacia recalled when her grandmother became very sick from complications due to diabetes. “She ended up getting a silent stroke, and then another that we didn't even know about, and so slowly, but surely, she lost her mobility.” Her grandmother was soon fully paralyzed, though they could still communicate through facial expressions. “The family would take shifts talking with her. I remember I was about 18, and I started telling her about my best friend in high school getting married, and that I couldn't believe it. We'd just graduated a year ago, and I was so happy.” Dacia remembers a single tear going down her grandmother’s face.

“She slowly decayed into a vegetable. It was horrible to see such a full-of-life person die that way. My grandfather did not want her in a nursing home, and so he fought tooth and nail for her to be there, and gave her whatever he could.” Dacia’s voice rose and fell with the cadence of her story, and with a confidence that came from a comfort and pride in telling it. “He was not a rich man by any means, but he did what he could. When she finally did pass, my grandfather went up to her, kissed her in the coffin, and whispered, ‘I'm done, mija,' which was a term of endearment. Then three months later, he was gone. He held on, just for her.”

Dacia’s father and mother were both born in the United States; neither spoke Spanish growing up, an intentional choice by their own parents. “My grandparents saw that there was a lot of discrimination going, having come to the US before the Civil Rights era, and so they tried to ‘Americanize’ my dad and make him as white as possible; look white, act white, talk white.”

Dacia and her brother, Matthias, grew up with a similar mentality. They looked down at Latin music, didn’t have any interest in speaking Spanish, and rarely engaged with their family’s history. Her brother, Matthias, told me about the first time he became explicitly aware of his identity. “I came running up to my dad one day, and told him that this other kid called me a bad word. My dad asked what he called me. ‘He called me a Mexican! ’”

It’s been a decades-long and ongoing process for Dacia to embrace her own history. “Ultimately, you can't change the color of your skin,” she told me. “You can't change cultural things. The way you show respect for elders; food, music, language.” She’s since fallen in love with Latin music, and is actively learning Spanish. “It shouldn't have been like that,” she said, noting her previous disdain for both. “The only reason that it was there was because my elders were trying to protect their kids from discrimination.”

She noted, though, that pride in her Hispanic culture wasn’t the same as finding her full identity there. “It’s fun right now to say that I'm Latina. It's ‘culturally relevant’ to be able to celebrate that. But besides that, I don't find my identity in that. Because it's just a part of life; it’s culture. And it's going to be different for every different Hispanic person that you ask: what does it mean to be Hispanic?”

Dacia with her brother, Matthias

Davar’s own relationship with his ethnicity, and its role in his identity, is more ambiguous than Dacia’s. Our conversations took place within the backdrop of the 2020 racial unrest in the United States, and at times Davar seemed uncertain whether his story should, or shouldn’t, explicitly acknowledge that backdrop. He’s confident about his own story and his own experiences, but less so when he imagines what others presume his story or experiences to be.

Davar with his mother and father

“I don't know what ‘the world’ thinks of our relationship,” Davar told me. “It’s not like I ever forget that I'm a Black man or that there’s racism out there, but I live my life not worried about it until something happens. And so that's it.” He gave me an example. “I drive for Lyft,” Davar began, “and so I picked up my passenger, who was also a Black guy, from the airport. There were two cops on their motorcycles checking that every car passing through had the proper ride-share permits.” The officers asked for some registration information. “Without even thinking, I reached for the glove box. And like, two or three seconds later, it hit me: I’m in my glove box.”

“Nothing happened,” he said, sounding as if that were both a relief and an obvious expectation. “The officer checked everything and let me go.” Davar texted Dacia afterwards: “I got stopped by the cops. Reached in my glovebox, I’m alive *tears emoji*”

“So I'm in this heightened state of emergency mode that entire time,” Dacia said, recalling her side of the incident, “not knowing what emotional state he’s going to be in when he gets back. But he’s fine, totally fine. So that’s one… of our… yeah.” Dacia didn’t finish the thought.

Davar and Dacia together after their reception

Many of Davar’s own reflections about his ethnicity are more about how he and Dacia are learning to see each other fully. “I’d like her to see me as not just a man, but as a Black man. Because being Black is a part of being the man she loves.” He said the same thing also applied to how he wants to see Dacia. “I know that I fell in love with more than just a woman; I fell in love with a Latina woman. And so I get what comes with that; the culture, the family, the food.”

Davar and Dacia together after their reception

The two have playfully fought over what their kids are going to look like. Davar thinks they’ll look Black; Dacia thinks they’ll look Mexican; both think that how they look will come second to who they are, and where they come from.“The love story that I told you about my grandparents,” Dacia said. “I didn't focus on all of the negative things, because that wasn't my family history. I'm proud that I have something to make of myself because of the sacrifices they made. And I want my kids to be able to feel that too, from both sides.”

Dacia and Davar run a joint instagram account called @interracialstephens where they regularly post pictures of themselves. Their goals with the page were, at first, more family-oriented. “At first, we wanted to post more pictures for our families,” Dacia told me, “but our individual social media tends to be more for business, so we made this one.”

One of the posts on Dacia and Davar’s joint instagram account

“There's a little part of it, though, where we want to normalize this kind of relationship, so it’s not ‘weird,’ and just feels normal,” Dacia continued. “I’m one of only a handful of interracial marriages in my very large family over three generations, and I wanted to basically call out the elephant in the room, and not just let everyone ignore it. I didn't marry a Mexican man; I married my Black husband. And I love that, and I have to get used to that, because for a while, in the world I grew up in, calling out that difference would be offensive.”

The two aren’t certain where they want to take the page, but part of its charm is that it doesn’t have a specific purpose, because it doesn’t have to. No couple needs to have a reason to post pictures together, embarrass one another on social media, sing captions of praise and longing and endearment, other than that they love one another dearly, and want to spread that love to others.

Another post on Davar and Dacia’s joint instagram account

After many months of COVID weddings that looked nothing like traditional weddings of the past, Dacia and Davar’s wedding was a welcoming, if restrained, return. The entire day was held outside at Bella Fiori Gardens, an attractive, well-manicured event space wedged between long stretches of Washington farmland. Their guests, about 50 total, mostly wore masks except while taking pictures and eating. Some maintained more cautionary distances than others. A few people hugged; many did not. Everyone felt a sense of joy to simply be there.

Dacia and Davar’s recessional

Davar’s uncle Howard was originally supposed to perform the ceremony for him and Dacia, but unfortunately passed away a few months before. “He was a huge influence in my life,” Davar said, “and was my pastor since 12 years old in Ohio. He always had an answer when I had a question about Scripture, telling me to look up another version or find context in this other place.” One of Dacia’s father’s best friends from childhood, and a close family friend, performed the ceremony instead.

They catered dinner from a local Mexican restaurant—Dacia’s family was friends with the owners—and both Davar and Dacia’s fathers and brothers gave toasts. The two shared a first, father-daughter, and mother-son dance, and Davar shared a video he’d made of the video clips he’d taken throughout their relationship.

Photos from Dacia and Davar’s wedding reception

After the wedding, Davar, Dacia, and I drove together to their hotel to get a few final photos. Along the way, we stopped at a local coffee hut. As we pulled up, the young barista began her normal greeting before stopping. “Hi, welcome, what can I get for AWWWW.” Noticing Dacia’s dress and Davar’s suit, her body seemed to dissolve as her knees collapsed and her hands cupped over her mouth in elation. She called her coworkers to come over too.

Davar and Dacia chatting with the baristas

“This is the cutest thing ever,” one of them said as Dacia and Davar posed for a picture. Dacia and Davar were happy to share their joy, and even happier when the drinks came on the house. “I should wear a wedding dress more often,” Dacia joked.

Davar and Dacia checking their drinks

Davar and Dacia are both excited about the life they’re building together in LA. “We're more focused on career right now, and laying down the foundation for a family,” Davar told me.

“I can't wait to be a father though,” Davar said. “A few days ago, I saw a father with his daughter, who looked about three or four, sitting on the sidewalk, just watching him get something out of the car. She sat there, waiting for him, and I was thinking about how I can't wait to be able to have my own child, who trusts me enough to listen when I tell them to wait.”

Davar and Dacia in their hotel room after the wedding. The two committed to abstinence before marriage, and wanted photos before. (Don’t worry, this photo was posed, and I left right after!!)

“But,” he continued, “I want to spend time learning how to be a husband before having to tackle being a father at the same time.”

Dacia has a little less patience for waiting to have kids. “I love, love kids,” she told me, “but I did not want kids of my own for the longest time. I was actually praying, ‘God, is there something wrong with me?’ And I felt Him just kind of whisper back, ‘I made you on purpose, the way you are, and the reason why you're like this is because I want you to do other things. When the time is right, I will make sure you have the desire to have children.’ And it did eventually wake up in me.”

Dacia with her flower girls

(Davar has a project where he posts a photo every day; one once touched on the subject that he doesn’t want kids right now, while Dacia very much does.)

“I was once going to fly to Illinois to visit Davar and his family in Ohio,” Dacia told me, “and my mom asked if Davar was going to meet me there and drive together. I said yes, and my mom replied, 'Good. Because I know that you can do it on your own. But, it's nice to do it with someone else, too.’”

Her words were emblematic of Davar and Dacia’s next chapter in life; both have spent the past decade building lives on their own. But, now, it’s nice to build with someone else, too.